| NEWBURY - Even the Boston Society of Architects, which gave it an award for good design, announced: ''We wouldn't want to live here.''

And the designer, Keith Moskow, begins his own PR blurb with the words: ''The Hall-Dorval house is not for everyone.''

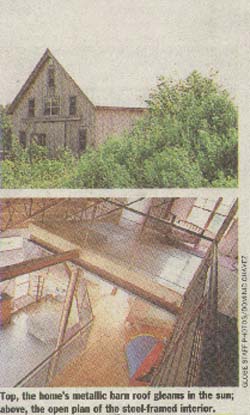

They're missing the point. Houses shouldn't be for everyone. It would be a bland world indeed if they were. This house, on a rural site in Newbury, is right for the family that lives here. It's gritty, industrial, informal, like the garage-rock ethic it echoes.

That's not to say it isn't also a little weird. Here are three examples:

An enormous granite rock sits in the middle of the living room, like the guest who never went home. The owners, David Hall and Lisa Dorval, say they wanted a natural rock hearth. Lisa took a golf cart ride through a quarry to pick out this 7,500-pound chunk of granite. It's not a hearth yet, but it already gets a lot of use. The kids, Jacob, 5, and Ella, 2, perform on it, using it as the center ring of impromptu circuses.

Eventually, Hall plans to hollow out the top surface, hang a metal chimney above, and call it a fireplace.

Or take the sauna. It's a wood cylinder sitting out in the woods. Once it was a vat in a now-abandoned tannery. Hall cut a hole in the side, installed a stove, and voila! a sauna. To celebrate moving into the house a few months ago, Hall and Dorval threw a party for the construction crew. They fired up the sauna and also a back-porch Jacuzzi. Guests cycled through either or both, then moved on into the hands of two hired massage therapists. Hall plans to improve the sauna with an insulated lining and a permanent roof. Eventually.

Or there's the traveling crane. Like something you'd find in a shipyard or stoneyard, this heavy steel beam rolls on tracks across the second-floor ceiling. A cable hangs down, from which the kids swing Tarzan-like. Eventually - there's that word again - the plan is that the cable will attach to a sofa. The sofa will swing from it, and also will be able to be transported across the floor to follow the sun.

|

Forever unfinished

You get the idea. One, the house is made of salvage, things picked up here and there, junk if you want to call it that. Two, it's never going to be finished because there's always going to be more salvage. Just recently, Hall bought a dozen 12-foot granite slabs left over after renovations to Boston's Prudential Center. ''We'll figure out something to do with them,'' he says.

Hall and architect Moskow are partners in a company that buys, renovates, and leases old buildings. Their renovation crew built the house, with help from the owners and friends. Cost was minimal: So far, the owners figure, they've spent $44 per square foot of floor area - not counting all those snacks for the friends.

|

|

| Living here is like rattling around in a big industrial loft - but a loft in the country. The property is 15 acres, and it faces directly onto 600 acres of Trustees of Reservations land, which will never be developed. David, Lisa, Jacob, Ella, and Buster (the Australian terrier) share the site with coyotes, deer, foxes, and owls - and monster salt-marsh mosquitoes. (There will be a screened porch ''eventually.'') Indoors, everything is wide open: Only the bathrooms have doors, or at least will have them eventually; for the time being, curtains serve. Even the bed in the master bedroom loft is screened only by its headboard, not by walls.

What they didn't want

''A lot of the houses we buy and renovate are 18th- or 19th-century places in Newburyport,'' says Hall. ''Rooms are small and dark and ceilings are low. We knew we didn't want that.''

''We'd been living in a small place,'' says Dorval, who's a psychotherapist in a group practice. ''Jacob is very active; he needs to be riding a bike, or swinging from a rope, or building something. We wanted a fun place, not precious, not where you'd worry if stuff spilled on the floor. It's like having a gymnasium.'' She's used to alternative housing: As a girl, she and her family spent summers in a trailer with a front porch on Lake Winnipesaukee.

For Moskow, the architect, the problem was how to think backward. ''Normally you design the house, and then you acquire the building materials,'' he says. ''This time, we had the materials first and we had to figure out how to organize them into a house. It was like having a kit of parts, but not all the parts were from the same kit.''

|

Tree bed and secret door

A special gem is young Jacob's room. Hall built a sort of open tent around the bed, made of white birch branches with the bark left on. ''As a kid I'd always wanted a tree bed,'' Hall admits. There's also a ladder, Jacob's ladder, that rises to a private loft from which a ''secret door'' opens onto an attic level.

Both the owners and their architect tend to joke about the house, a little nervously, as if they felt slightly embarrassed. Maybe they think it feels too hippie for the 1990s. They shouldn't. Not only does it offer a breathtaking sense of openness and space, rather like the backstage of a theater, but it also offers the subtler joys of architectural punning: a sauna that is also a tanning vat, a deck rail that ought to be somewhere out on Route 1. There's pleasure in that kind of transformation of found objects from one purpose to another. An artist like Marcel Duchamp would have loved the house.

It may not be for everyone, but Hall gets it right when he says: ''Living here is phenomenal.''

| |